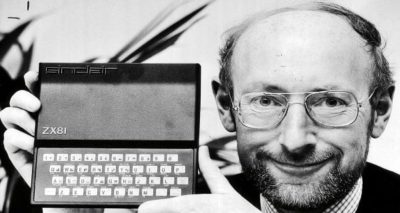

It was an incredibly sad week for British computing last week, as Sir Clive Sinclair, creator of the ZX Spectrum died aged 81. He was the founding father of the British home computing industry – our Steve Jobs. He was not as successful as Jobs, but had a life richly filled with prolific invention and innovation.

Largely self-taught, he began inventing gadgets while he was at school. His passion was for miniaturisation. In 1962 he set up Sinclair Radionics, aged 21, in his flat making cheap pocket radios – the Sinclair Slimline – dispatched to customers via mail order, a new business model at the time.

The Sinclair Executive, a slimline calculator, came in 1972. The most portable pocket calculator of the age was ahead of its time. It sold for £79.95 (about £1,000 in today’s money) and cost only £10 to make. It offered only basic maths functions but sold in the thousands. So-called pocket calculators in those days were closer to the size of a brick, so Sinclair took the chip, reduced its power consumption by switching it on and off, so it was only on for 10% of the time. As a result, instead of having great hefty batteries, it had hearing aid cells, was only 8mm thick and would just slip into your front shirt pocket.

In 1975, in a similar vein, Sinclair designed the first plastic watch with a single chip. It was produced as a kit version at £17.95 and £24.95 ready-built (£200 in today’s money). But this had problems, including a short battery life and faulty casing. Sinclair’s next project was to design a slimline television and a pocket television, also both well ahead of their time, but failed to take off.

In 1979, Sinclair moved into computers. His breakthrough was the ZX80, followed by the ZX81 and ZX Spectrum. It’s hard to overstate the importance of Sinclair’s role in the world of computing. His ZX Spectrum home computer sold five million units and radically changed the perception of, and access to, computers. His work created the path to not only gaming, but also the creation of games.

Sinclair became a household name. That ZX cost just £49.95 as a kit, £69.95 pre-built, and went on to be the biggest selling home computer in both the UK and the US. Then came the iconic ZX Spectrum (‘The Speccy’), most popular in its 48K and 128K formats, a huge step in British computing towards the Atari, Amiga, and the home PC.

With no commercial rivals, Sinclair sold a quarter of a million of the 1981 model in the first year. By 1982 he had turnover of £27m; a year later the company was valued at £136m and the profits had reached £20m. If many owners used their computers to play games they were also taught about programming and other technological skills. I wasn’t a geek but had a ZX81and did my first BASIC programming at school.

I remember seeing the instruction manual for the first time and I understood straightaway that the thing my teacher was plugging into the TV was the future. My maths group sat around the screen and took it in turns to type in one of the BASIC program listings from the booklet. The result was a game in which you had to input coordinates to throw a ball into a waste-paper basket. It was amazing. There was something on the TV that we’d made, and that we could interact with.

Via the BASIC programming language on the ZX, homebrew development boomed, leading to the formation of the cottage industry. You can draw a direct line to Grand Theft Auto – DMA Design was a group of amateur Spectrum developers meeting at a computing club, eventually creating Lemmings, then later GTA. They became Rockstar North, and you know the rest.

The affordability of Sinclair’s revolutionary home computer let a generation of young bedroom coders make anarchic, punky games, and its hardware limitations merely fostered extra creativity. The hobbyist computer market, which introduced the likes of Bill Gates and Steve Wozniak to programming, was not as well-developed in the UK, but you could buy the ZX81 in Boots or WH Smiths or from the Argos catalogue. It was more affordable than the competition – the BBC Micro, Commodore VIC-20 or Apple II – so teenagers received them for Christmas and began making their own games.

Far too many obituaries of Sir Clive are obsessing on his later failures, most especially his wonderfully ambitious C5 electric vehicle, decades ahead of the rest of the world. The failure of the C5 is a woeful distraction from the world-changing effect of the ZX, and undermines his successful drive to make computing accessible to people.

The C5 was a three-wheeled, lightweight, open, plastic-sided vehicle, launched in 1985. Retailing for £399 with a top speed of 15mph and whose battery needed recharging every 20 miles, it was rushed into production, with Sinclair predicting annual sales of 100,000. But its flaws were only too evident and it sank under poor reception. The market had been led to expect a full-sized vehicle from the genius inventor, not a tricycle with a modified Hoover washing machine engine. It was a financial disaster.

Within months Sinclair was forced to sell his computer company to Alan Sugar, the owner of Amstrad. Sinclair was suddenly transformed from bearded boffin wizard to a figure of fun, a cross between Einstein and Willy Wonka. The same year The Guardian described him as one part visionary, one part dotty uncle and one part marketing genius.

Sinclair Research continued to operate as a small research and development company. He was still fixated by the idea of an electric vehicle and in 1992 launched the Zike, a lightweight electric bike. Like the C5, it failed to sell, but he remained one of Britain’s great innovators who could turn his dreams into reality. The idea that an inventor can come up with some brilliant idea and somebody else will make it all happen is nonsense he once said, Either you do it yourself or it ain’t going to happen.

Currently there’s an army of startup innovators working on high impact and daring ideas, like Sinclair did all those years ago. These ground-breaking ventures, with sweeping visions and big hairy audacious goals, operate under the influence of outsize creative thinking, and employ audacious strategies. But choosing which innovative idea to pursue is often serendipity or a ‘light-bulb’ moment like Archimedes had relaxing in a bath before discovering his famous principle.

Innovation is notoriously hard. Some tinker and tweak, but the reality is innovation requires you to reframe your mindset, put aside the prevailing reality and underlying ‘rules of the game’ which requires bold, brave thinking. Startups innovate by examining each core element of their business model, which typically comprises customer relationships, key activities, strategic resources, the cost structure and revenue streams. Within each of these elements, various business-model innovations are possible. Here are some examples.

Innovating in customer engagement: from loyalty to empowerment Customer loyalty is seen as a key business goal, but the pursuit of loyalty has become more complicated in the digital market. The cost of acquiring new customers has fallen, customers, enabled by digital tools and extensive peer-reviewed knowledge now often self-select their buying options. Innovation embraces the paradox that goes with this – the best way to retain customers is to set them free – pay-as-you-go and the Freemium model are attractive pricing strategies to gain early customer traction.

Customer engagement innovations are all about understanding the aspirations of customers and using those insights to develop meaningful connections between them and your company. Airbnb executes this brilliantly, leveraging personalisation, automation, simplicity and intimacy.

Innovating in activities: from efficient to intelligent Here the focus is to spend less time on optimising processes and instead build flexibility and embedded intelligence directly into them to improve the customer experience. In essence, digitisation is empowering to go beyond efficiency, to create learning systems that work harder and smarter.

For example, a web-based hotel-booking platform reframes the focus of the hotel business model from availability to user choice and self-selection. We look for more than convenience, simplicity and speed, and focus on content. All seek to raise the click-through rate. AI tracks individual customers’ preferences and behaviours.

Innovating in resources: from ownership to access Businesses use to compete by owning the assets that matter most to their strategy, and at scale, to be the best way to ensure reach and access for customers. Banks and Retail are the best examples of this. Now it’s online, increasing transparency and reducing time and transaction costs, enabling new and better value-creating models of collaborative consumption.

As a result, ownership may become an inferior way to access key assets, increasingly replaced by flexible win-win commercial arrangements with partners, best shown by AirBnB. As with all the business model innovation highlighted here, putting the customer at the heart of the business model is the fundamental paradigm shift.

Innovating in costs: from low cost to no cost What’s driving prices in innovative digital models is the reframing that customers can simultaneously be scaled and replicated at zero marginal cost. Mobile phones is a good example, where the previous dominant belief has been that value is best captured through economies of scale – the more telephone minutes sold, the lower the unit cost.

Now pricing has moved from text and voice plans by focusing the economic model on making money from data usage and investment in data networks and storage capacity. We’ve seen tariffs split between handset and service supply, and a plethora of pricing menu options to suit the individual consumer. We have the Freemium model backed up by bundling of products and services, where the handset is ‘free’ as an option and consumers pay for additional, premium services. This has been hugely disruptive.

Innovation in networks: connect with others to create value in the connected economy. Collaborative networks enable startups to leverage other companies’ brands, processes, offerings and channels through strategic partnering. This network innovation means firms can capitalise on their own strengths and share risk, while harnessing the capabilities and assets of others, develop new offers and ventures. Amazon is the best example of network innovation, which ensures its growth is driven by customer insight and intelligence gathered by network effects.

Innovation in service: support and amplify the value of your offering Service innovations enhance the utility, performance and value of an offering. They make a product easier to use and highlight features and functionality customers might otherwise overlook. They also fix problems and smooth rough patches in the customer journey and bad customer experience in the current product. Done well, they elevate products into compelling experiences that customers come back for again and again. Uber’s technology is a great example of this, which fundamentally changed the taxi-passenger experience, yet still provided the identical core transportation offering.

The process of identifying and delivering these innovations needs intuitive visions of the future to carefully scrutinised strategic analyses. Within this, one of the hardest things to figure out is when to kill something. Both are lessons from the innovations of Sinclair.

For innovation, you need the mindset, determination and curiosity of an entrepreneur, and to be bold and brave. When we all think alike, nobody is thinking. You need to see what everybody has seen and think what nobody has thought, and don’t live your life in the rear- view mirror – it tells you where you’ve been, not where you can go looking forward.

So work hard on reimagining and reengineering your startup business model, put customers at the centre of your thinking, just like Sinclair, and give your startup an unfair advantage. My old ZX81 is long gone, last week I wish I still had that funny-looking home computer, and with it, like all innovation, a look into the future.