I’m still wading through the books I got for Christmas. I’m easy to buy for, I give my wife a list of about twenty books I’d like, and she runs the Amazon buying cycle through friends and family to ensure I am never disappointed. The best this year was a collection of Bletchley Park codebreaking, maths puzzles, IQ tests, and crossword books from my son James. Fiendishly challenging and some downright impossible. I would not get into Spy School.

My default reading is non-fiction, but I do like a good novel, brimming with deep characters and a compelling, fast-moving plot. Ever since humans started to create cave paintings, we’ve used stories to communicate, from gatherings around campfires to traveling poets. Billy Connelly masters the art of storytelling for me, using humour to bring vitality and imagery to his yarns. Storytelling is a powerful mechanism for sharing insights and ideas in a way that is memorable, persuasive, and engaging, so how can a startup founder use it as a tool when seeking to connect with early customers?

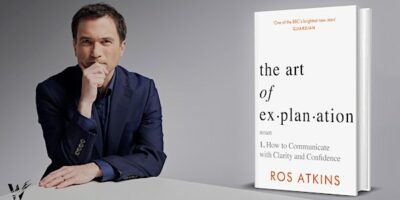

There’s lots of content on the web advising on how to use storytelling in your startup, but I’ve got a different perspective from reading one of my Christmas books – The Art of Explanation, by BBC journalist Ros Atkins, where he shares the knowledge he has gleaned from years of working in high-pressure newsrooms, identifying the ten elements of a good explanation and the steps you need to take to express yourself with clarity and impact. The Art of Explanation is a good read for founders who want to sharpen their product pitch to potential early adopters. It’s an incisive and accessible guide to how to articulate yourself. Do you worry about holding people’s attention during such presentations? Are wondering how to get all your points across succinctly?

Most of us are not subject to the demands made on TV news journalists such as Ros. They must, in just hours, familiarise themselves with a topic, decide which information is reliable, vivid and important. They must then connect these into a logical sequence without gaps, non sequiturs or distractions and deliver this information to camera convincingly. Ros’s book showcases a technique to catch, sort, grade, clean, fillet, pack and deliver information.

Many steps-to and art-of books, however competently written and well meant, are not fully credible, or are compelling examples of what not to do (Trump’s The Art of the Deal). Atkins has no such problem. Anyone who has watched one of his three-minute backgrounder videos on the BBC will have gone through the same stages of delight and disbelief as I have.

Atkins argues that the space for facts inside people’s heads is not rent-free and must be earned. Everything must either contribute to the push to shape their thinking or be gone. If you’re expecting shortcuts, you’ll be disappointed. Atkins calls it assertive impartiality, a thorough presentation of the facts as a briefing to make a decision, rather than simply being a passive listener pitched to. Every step of this process is beautifully explained, with examples taken from his own experience.

Atkins is engagingly self-deprecating and generous. This is not a dry manual. I loved the part where he credits Steely Dan for the idea that the final stage, after everything has been trimmed, tightened and smoothed, is to loosen the belt a notch and make it all sound relaxed. This relaxation prompted one colleague to ask how he managed to deliver a whole hour unscripted. The answer? Every word was scripted.

The art of selling an unproven product to earlier customers is an emotional one. You need to be able to tug on the heartstrings of the person on the other side of the table, but also eloquently convey your value and make them feel like they’re missing out if they don’t buy.

Before you even think about starting to talk to customers, you need to think about why they should buy from you ahead of anyone else, including potentially ditching an existing supplier with a proven product. Be bold, but I don’t mean you should recreate a Jetsons episode with talking robots and flying cars (unless of course, you are building either of those things!).

Here are the ten pillars of thinking from The Art of Explanation: How to Communicate with Clarity and Confidence that provide a useful framework for your customer pitch.

1. Simplicity. Is this the simplest way that I can say this? If what we say is in its simplest form, it’s going to be easier to take in. Show, don’t tell Share the story so it unfolds naturally. As Mark Twain said, help people to answer the question What does this looks like in practice? Sculpt your story by using simple anecdotes, with a sense for what customers may think of as interesting angles.

2. Essential detail. What detail is essential to this explanation? Add to their thinking, for example:

- Identify the tailwinds in this market, categorise them as High, Medium or Low with regard to the magnitude and importance on the customer.

- Focus on where your solution mitigates these and what their business could look like with you on board. Sharing this with customers confirms your credibility and knowledge.

3. Complexity. Are there elements of this subject that I don’t understand? We need to understand the subject fully ourselves if we’re to explain why our solution works. You can’t avoid the complexities of showing an awareness of your customers problems.

4. Efficiency. Is this the most succinct way that I can say this? The more efficient we are, the more space we have to include essential information only – and the more we give people in return for their time.

5. Precision. Am I saying exactly what I want to communicate? We don’t always say exactly what we mean. Double-check if the words you’ve chosen match what you hope to get across. Offer the missing piece of the puzzle. Demonstrate possibility by showing what needs to happen, and again show simplicity and detail.

6. Context. Why does this matter to the people I’m addressing? Potential customers are far more likely to want to hear what we’re saying, if they’re convinced it matters to them.

Spark intrigue. I think we can do something remarkable about this. They will prick up their ears. They may not roar with excitement but make them aware of where you’re heading, and just maybe, they’ll want to come along with you.

If you are a pre-revenue startup, this task is hard but it’s still possible to tell a good story without traction, but you’ve got to be smart about it. What are your prospects’ key metrics for success? Show how your solution can drive improvement in their metrics.

7. No distractions. Am I including verbal, written or visual distractions? We all frequently include information that works against, rather than supports, what we’re trying to communicate. Build trust. Remove uncertainty from your pitch by giving a demo. If you’re an early-stage startup, use demos and videos to show the reality of what success could look like for a customer.

8. Engaging. Are there moments in my explanation when attention could waver? If we lose someone, whatever we have to say next may not register. Agitate the problem. If we do nothing, this is where we are heading. Show that we’re at a pivotal moment. If we don’t act now, things will get much worse. Create the picture of the future opportunity.

9. Useful. Have I answered the questions the customer has, or have I just spoken to my script? If we address people’s questions, there’s a greater chance that they are going to want to hear what we have to say.

10. Clarity of purpose. Above all else, what am I trying to explain? If we can be clear on this, the decisions that we make about which information to include, and which language to use, will become a lot clearer too.

It gives you safety, security, and a complete affordable solution. Tell the customer exactly how your solution will benefit them and why, not listing the features. Bring the solution alive and make it personal to them, so they come to their own conclusions. People don’t just absorb facts and information, they listen to make their own inferences.

I think this ten-step framework gives you the best chance of communicating well. If you find them useful too, check out The Art of Explanation which has more detail along with practical advice on a range of different types of written and verbal communication, and the stories behind the advice.

Good stories surprise us. They make us think and feel. They stick in our minds and help us remember ideas and concepts in a way that a PowerPoint crammed with bar graphs never can. Successful founders need to be poets of the future, engagement is no longer about the stuff that you make, but about the stories you tell. The purpose of a founder storyteller is not to sell to customers, but to help them think differently, and to give them questions to think upon.